Introduction

Most of the information in the world today is collected, transferred, saved and processed

digitally. With digital information becoming ever-present in our daily lives, incidents of computer crime are

on the rise. Increasingly, criminals are adopting various technological means to enable their offending,

obfuscate evidence and avoid prosecution. Law enforcement has found itself in a continuous battle as new

methods are devised to commit crimes, in response new procedures must be

developed.

The field of digital forensics is still young and emerged in response to a growing amount of computer

related crimes. Its origins can be traced back to the FBI and similar agencies, when they began developing

programs in the late 1970s to examine digital evidence. There is no single answer to ‘what is

digital forensics’, however it can be broadly described as 'the process of identifying, preserving, analysing,

and presenting digital evidence in a manner that is legally accepted'. The investigative

approach is extremely important for a forensic examiner, they must ensure the absolute credibility of any

evidence obtained. Overlooking a step or mishandling information can lead to inconclusive or poor results

and a culprit may escape conviction, or an innocent suspect could be subject to negative consequences.

Technicals & Procedures

As opposed to simply examining devices or analysing data, the fundamental

goal of digital forensics is to offer legitimate and accurate digital evidence for

court cases. It does not solely focus on technical problems; it encompasses

both computing methods and legal issues. It is multidisciplinary in nature, dealing with arrests, seizures, preservation,

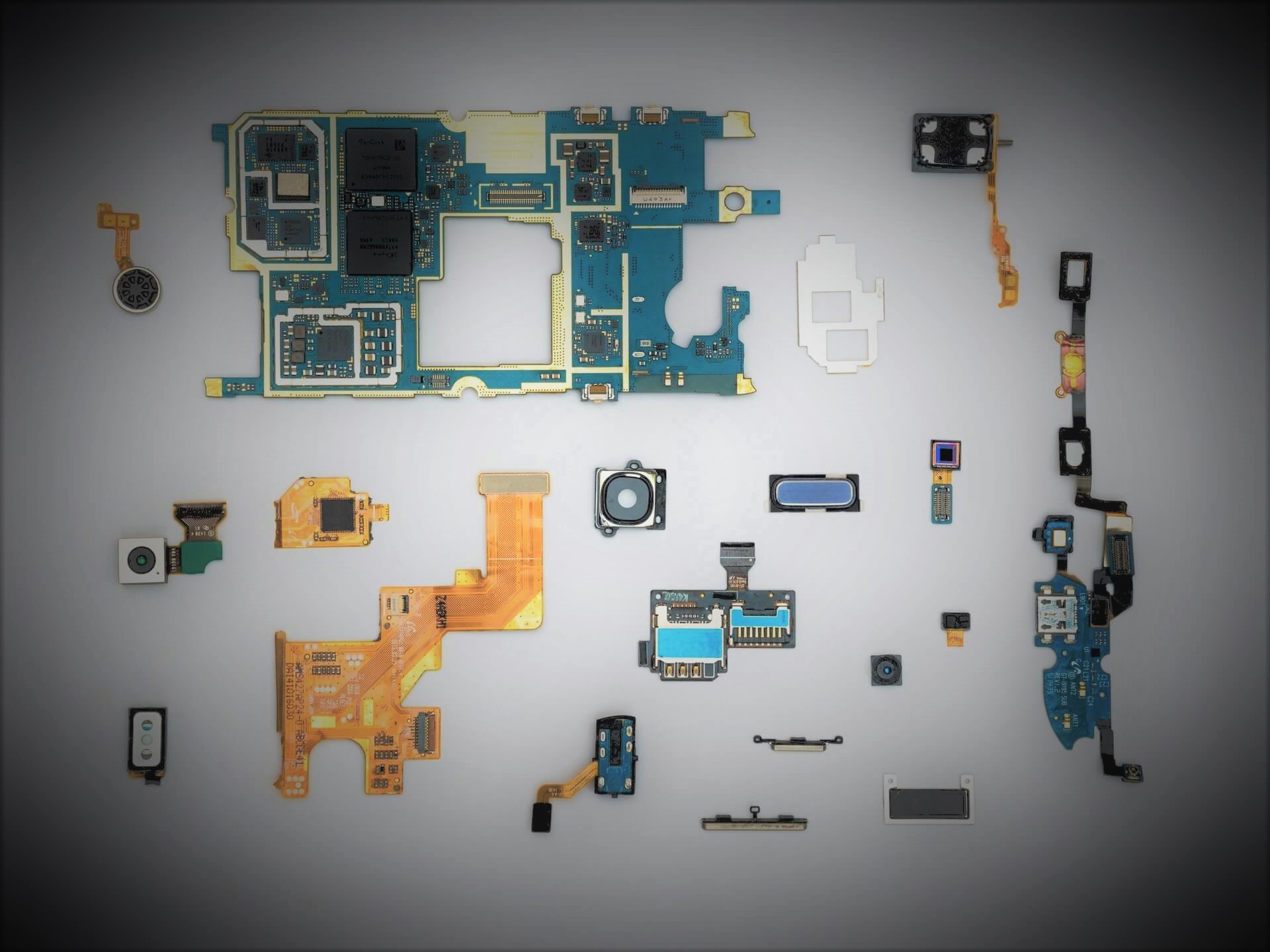

investigations and the storage of devices and objects. Digital evidence itself

comes in many different formats such as physical hardware, digital audio,

video and imagery, mobile devices, user logs, social media and other digital

communication platform history. Law enforcement has recognised that

modern day life cannot be adequately protected without considering the wide

variety of digital devices and systems that can be exploited. Unfortunately, due

to the overwhelming amount of digital information being collected, there is a

significant lack of resources to competently analyse all the evidence. As such,

there is a large backlog of pending criminal cases with thousands of devices

awaiting examination.

Our digital footprint is enormous and provides lots of information about the

webpages we visit, the actions we commit, when we were active on a system

and the type of device we were using. Following these footprints allows

investigators to retrieve data that is often crucial to criminal cases. Various

tools and software can be used to help experts when they are analysing

encrypted information and many different techniques can be deployed

depending on the type of crime being dealt with. Some of the tasks involved

with an investigators role include cracking passwords, recovering deleted data,

examining content on devices and determining the source of security breaches. Once all of the evidence has been collected, it will be stored and

made presentable for the police or courts to review.

The procedures for conducting an investigation should be flexible given the fast moving technological landscape. However, to limit

liability, ensure legitimacy, validity and reliability; some definition of a standard operating procedure is typically adopted. A number of

frameworks have been suggested, the DFRWS created a model in 2002 which consists of six phases and does well at providing general

guidance. Other institutions have also engineered models to approach the issue of a formal set of forensic

investigation rules, with some organisations distilling existing frameworks into their own policies.

Laid out below are the general procedures for a digital forensic investigation:

- Preparation

• Monitor, support and obtain authorisation to begin the investigation.

• Ensure that the infrastructure and resources are sufficient.

• Provide the mechanism to detect and confirm any incident.

• Identify the need for the investigation.

• Plan in detail the path to getting the required information.

• Identify and agree a strategy, policies and remit.

• Inform subjects involved that the investigation has begun.

- Acquisition & Preservation

• Establish what constitutes as evidence and identify potential sources of data.

• Determine the location of the evidence and details of incident.

• Translate any media into relevant data.

• Maintain integrity via write protection & hash checking.

• Package, transport and store the data.

• Ensure that the devices cannot be tampered with; maintain chain of custody.

• Record the details of any physical scene.

• Duplicate all digital evidence using accepted tools and methodology.

- Examination & Analysis

• Determine the author of the data and how and when it was produced.

• Record and highlight significant data points.

• Extract any hidden data or information stored within unconventional locations.

• Attempt to identify patterns in behaviour.

• Recognise clear digital evidence and assess the competence of the suspect.

• Transform the data where required into a more manageable format for analysis.

• Construct detailed documentation to assist analysis and form conclusions.

• Build a timeline of events and data.

• Create hypothesis of the event and document the findings.

- Examination & Analysis

• Prepare the results from the analysis.

• Determine the reliability and relevance of the information.

• Clarify evidence, statistics and provide an explanation of conclusions.

• Communicate the findings and prove the validity of the hypothesis.

- Resolution

• All physical and digital property is returned to its owner.

• Disseminate the data from the case.

• Determine which criminal evidence must be removed.

• Review the case to identify potential areas of improvement.

• Finalise the investigation and preserve the obtained knowledge.

Tools

A critical element of forensic analysis depends on practitioners knowledge of the limits, capabilities and restrictions of their tools. It is

not possible to calibrate and verify digital forensic tools in the same way as equipment used for analysing DNA or other scientific

evidence, there are simply too many variables. NIST has conducted thorough tests on the various features of leading forensic toolkits,

however there are more software applications and capabilities available than any one group can test, so forensic analysts are normally

recommended to perform some kind of validation themselves. Many organisations choose to develop their own test data incorporating

scenarios that they commonly encounter; this can allow them to test their tools and ensure that their interpretation of pertinent

information is correct. Even following validation of tools, experienced analysts will “trust but verify” any important findings. This could

include reviewing the data in a hex viewer, or repeating the analysis with a different forensic tool and confirming the same results are

achieved.

Some of the tools available and often used within the industry include:

FTK / Forensic Toolkit

This is an advanced password recovery and encryption breaking application that also offers full disk forensic imaging, registry parsing

with labelling and bookmarking and nice visualisation options all navigated with a modern and simple user interface.

EnCase

Securely analyse multiple machines simultaneously, triage and collect information from various locations. Unify evidence while

ensuring integrity, provides customed workflows and efficiently audit large groups of machines to identify fraud and security issues.

Sleuthkit

A collection of UNIX based command line file and system volume analysis tools. Inspects raw, EW and AFF file types and disk images. A

complete kit for investigating disk images and recovering files from them, review meta data, complete file structure analysis and

timeline generation.

Autopsy

Provides a graphical user interface for Sleuthkit. Complete offline or live analysis is done when used in combination with Sleuthkit.

CAINE

This is an open source Linux based distribution developed explicitly for digital forensic purposes. It provides a suite of existing security

tools all based around user friendly interfaces. It provides automatic extraction of timelines from RAM, and many tools such as

Autopsy, Wireshark and PhotoRec built in and ready to go.

SIFT

Another popular Linux distro focused on digital forensics and incident response. It automatically maintains the latest software with

tools and techniques for investigation.

Wireshark

This platform is one of the worlds most popular network analysers. It specialises in network monitoring and troubleshooting and

conducts deep packet browsing. It is multiplatform and has a substantial list of features.

Volatility

Tools within the Sleuthkit focus on hard drive discovery, however this is not the sole place where data could be stored. Important

forensic information is often found in RAM and this must be collected quickly and carefully. Volatility is the most widely recognised tool

for the analysis of volatile memory and is open source.

Registry Recon

A variety of data can be found stored in the system registry; malware is also regularly present within OS registries. Registry Recon is a

specialised tool that enables users to analyse and rebuild parts of the registry.

Cellebrite

This platform focuses on mobile digital forensics. It features a full investigative solution with a range of tools, the ability to check for

deleted data, breach encryption and the extraction of data from mobile devices make it a widely utilised application.

Evaluation & Importance of Documentation

There are still some drawbacks to the digital forensic techniques used today. To ensure compliance with traditional forensic

requirements, all data pertaining to an investigation must be collected and examined for evidence. Current computers could be holding

large volumes of data to be reviewed, which leads to lengthy timeframes gathering, storing and analysing data. Technology and the

crime it enables are rapidly changing, the systems under investigation are often evolving faster than the tools to examine them. Due to

electronic devices being so widespread, computer crimes are occurring across all jurisdictions and many areas lack the resources to

train and hire investigators.

Given that every investigation has its differences, it will remain difficult to fully determine a set of standard operating procedures.

Therefore, it is extremely important to deploy a methodical approach to organising and analysing the large data sets involved with

computer crime. Reconstruction of a scenario using forensic data allows investigators to gain a more complete understanding of the

situation, the acquired data lets us sequence events, determine locations and establish the time and duration of user actions.

Throughout an investigation it is imperative to maintain high levels of care and attention to documentation, the proper handling and

processing of evidence should mitigate any problems that could affect admissibility. The HTCIA adopted these guidelines to preserve

the admissibility of digital evidence:

1. Upon seizing digital evidence, action should not change that evidence.

2. When it is necessary for a person to access original digital evidence, that person must be forensically competent.

3. All activity relating to the seizure, access, storage or transfer of digital evidence must be fully documented, preserved and available for review.

4. An individual is responsible for all actions taken with respect to digital evidence while the digital evidence is in their possession.

5. Any agency that is responsible for seizing, accessing, storing or transferring digital evidence is responsible for compliance with these principles.

The absence of procedural standardisation further exacerbates the difficulties and effectiveness of current investigation techniques,

creating privacy concerns and hindering efficacy. Disparities in regional law enforcement operational requirements, training and

budgets results in different methods being used for preparing and presenting forensic reports. This can have a big impact on the end

quality of an investigators findings and there is a genuine need to develop a standardised set of procedures and specifications,

something that provides clear guidance to achieve a format that will be admissible across many jurisdictions. Generally speaking, the

methods used to collect evidence have been developed informally by investigators within the industry. The scope and legality of

digitally acquired evidence within criminal proceedings can sometimes be unclear and may not be rigorous enough for justice systems

standards.

Summary

The field of digital forensics has progressed with great speed, but more is needed as new interesting problems appear on the horizon.

With computers reaching ubiquity throughout modern society, they continuously change in shape, size, purpose and function. At one

point in time evidence could be gathered from large mainframes, however now we have personal computers, mobile devices, laptops,

cloud service providers and complex networks, all of which can offer digital evidence. Data located on a computer in the United

Kingdom could be readily available to another user across the world, spanning many legal jurisdictions.

It is crucial that this domain is given the attention and resources it needs to achieve fair and accurate outcomes. A poorly conducted

investigation, badly managed procedures and a lack of tools could have serious and far reaching consequences for all those involved.

Moving forward, challenges remain for investigators due to the sheer volume of data being captured. A single inquiry can contain many

terabytes of information, spanning across many device types and locations. Ensuring that this landscape is properly funded and

nurtured will have a profound impact on the future of the legal framework surrounding our digital lives.